Our march through Denver’s decades continues into the 1990s! This is the thirteenth post in our series exploring the geographic and architectural attributes of Denver’s single-family homes. For previous installments, please use the links below:

1870s (plus series introduction)

1880s

1890s

1900s

1910s

1920s

1930s

1940s

1950s

1960s

1970s

1980s

The 1990s was Denver’s fourteenth full decade as a city and also the decade it came roaring back from the difficulties of the 1970s and 1980s.

Perhaps the city’s lowest point came in 1986 when the full impact of the energy bust was felt across the city. The tower cranes that had dominated the downtown skyline for a dozen years were gone and in their place were shiny new, and mostly empty, skyscrapers. Property values tanked. People saw 50% of the value of their homes disappear virtually overnight. There were no jobs and the outlook was bleak.

By 1990, however, things were looking up. Mayor Peña’s visionary leadership and a slate of ambitious civic projects began lifting the spirits of Denverites and the city’s economy. By 1990, the new airport was under construction, and hundreds of millions of dollars of new libraries, bridges, and parks were underway thanks to the 1988 bond issue. In 1990, Denver citizens passed a $199 million bond issue to improve the city’s schools, and that same year, metro Denver voters approved a 0.1 percent sales tax for a new major league baseball stadium. Our faith in “If you build it, they will come” was rewarded in 1992 when Major League Baseball granted the Mile High City an expansion team—the Colorado Rockies.

We’re just getting started: In 1990, the new Colorado Convention Center (Phase 1) opened, as did the upscale new Cherry Creek Shopping Center, which gave Denver a huge boost in recapturing retail dollars from the many suburban shopping malls that ringed the city. Also in 1990, Denver voters approved a $90 million bond issue to build a new Central Library, several new neighborhood branches, and improvements to dozens of existing branch libraries.

Mayor Wellington Webb was elected in 1991 and continued to push a strong agenda for civic investment and infrastructure in Denver. In 1991, the Buell Theater opened in the Denver Performing Arts Complex, and in 1993, a half million Catholic youth descended on downtown Denver to celebrate World Youth Day. In 1994, Denver’s first light rail line—the 5-mile long Central Corridor through downtown—opened in 1994. Then, in the spring of 1995, Denver celebrated an amazing quartet of grand openings with Denver International Airport in February, the Denver Central Library in March, Coors Field in April, and Elitch Gardens in May.

The good times continued to roll throughout the rest of the decade. Denver snagged an NHL team from Quebec—the Colorado Avalanche—who promptly won the Stanley Cup, giving Denver its first major sports title. The city hosted the Summit of the Eight (G8) gathering in 1997 and, in 1998, voters approved another $95 million bond issue for neighborhood improvements and funding to build the new Mile High Stadium, while the Denver Broncos gave us back-to-back Super Bowl victories. A new aquarium and the Pepsi Center opened in 1999 and, by the end of the decade, most of the old viaducts and crumbling infrastructure in the Central Platte Valley had been replaced, paving the way for the valley’s remarkable redevelopment in the 2000s.

Finally, the 1990s was the decade when Lower Downtown transformed from a gritty historic area where urban pioneers began converting old warehouses into lofts and brewpubs, into the thriving mixed-use “LoDo” district where virtually every historic building had been renovated by mid-decade, and new construction started replacing parking lots.

From 1990 to 1999, approximately 6,100 single-family detached homes were built in Denver. This total was up from the 1980s by over a thousand units, but perhaps the bigger story about single-family detached homes in Denver in the 1990s was the pop-top phenomenon. Not counted in that 1990s total of 6,100 new units are the thousands of Denver homeowners who popped the tops off their smaller historic homes to add more square footage so they could stay in their favorite Denver neighborhood and have a bigger home too. Denver homeowners’ willingness to invest in their homes and in their city during the 1990s was a clear sign that Denver was, once again, a city on the move.

In the 1990s, Denver stopped its two-decade streak of population losses, increasing in population from 467,610 in 1990 to 554,636 in 2000, a 19% increase, and the second-largest (after the 1940s) numeric increase in one decade in the city’s history.

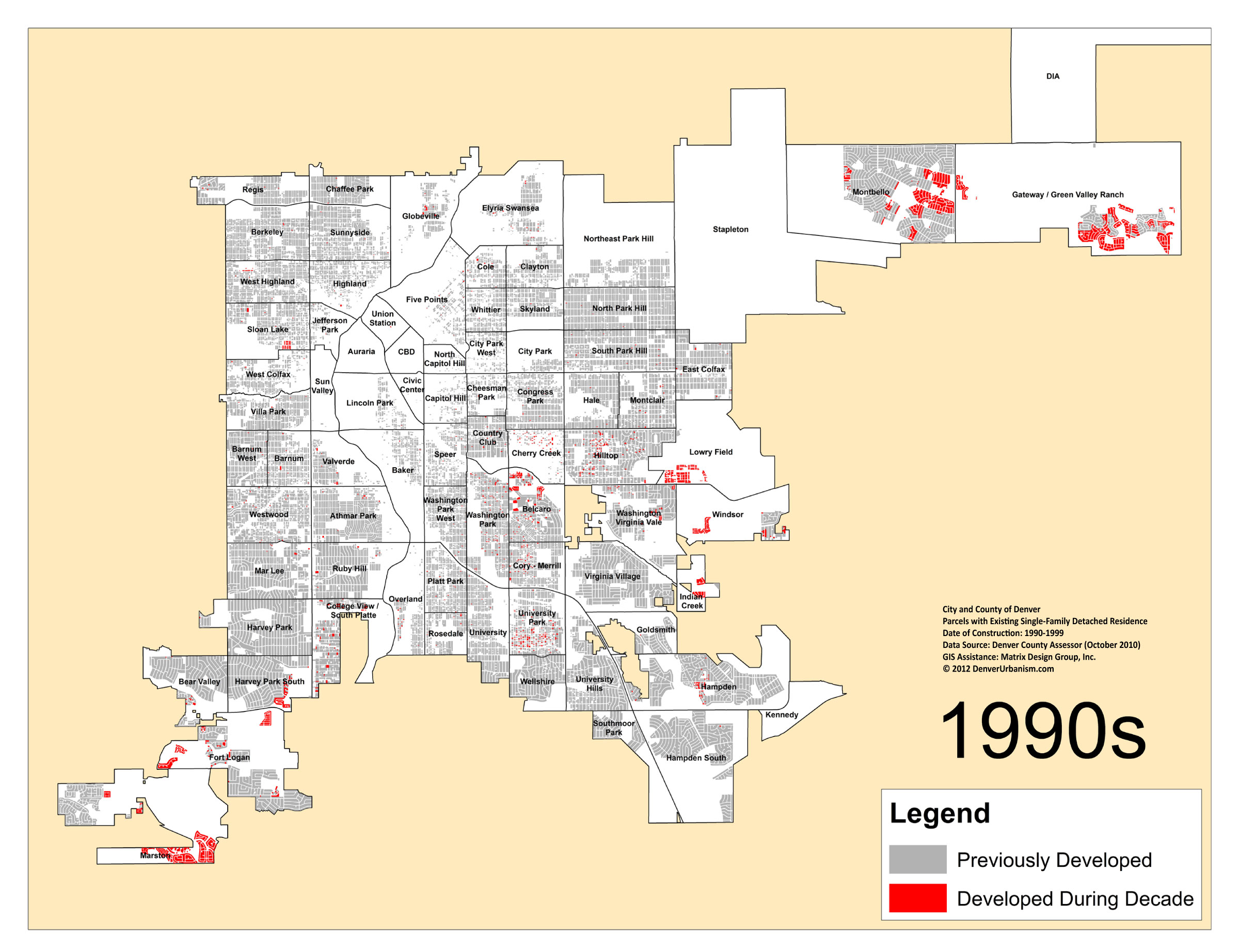

Here’s our Denver Neighborhoods Map showing the city’s single-family residential growth in the 1990s. Parcels with single-family homes built during the 1990s that remain in existence today are colored red. Parcels with homes that were built in a previous decade that remain in existence today are colored gray. Click/expand to see images at full size.

In addition to the obvious completion of new subdivisions on the city’s edges, in places like Marston, Montbello, and Green Valley Ranch, two other things stand out in this map: First, the beginning of the redevelopment of the former Lowry Air Force Base is visible. Second, if you look carefully, you can see red scattered throughout much of southeast Denver, particularly neighborhoods like Hilltop, Cherry Creek, Washington Park, Cory-Merrill, and University Park. Those are mostly scrape-offs.

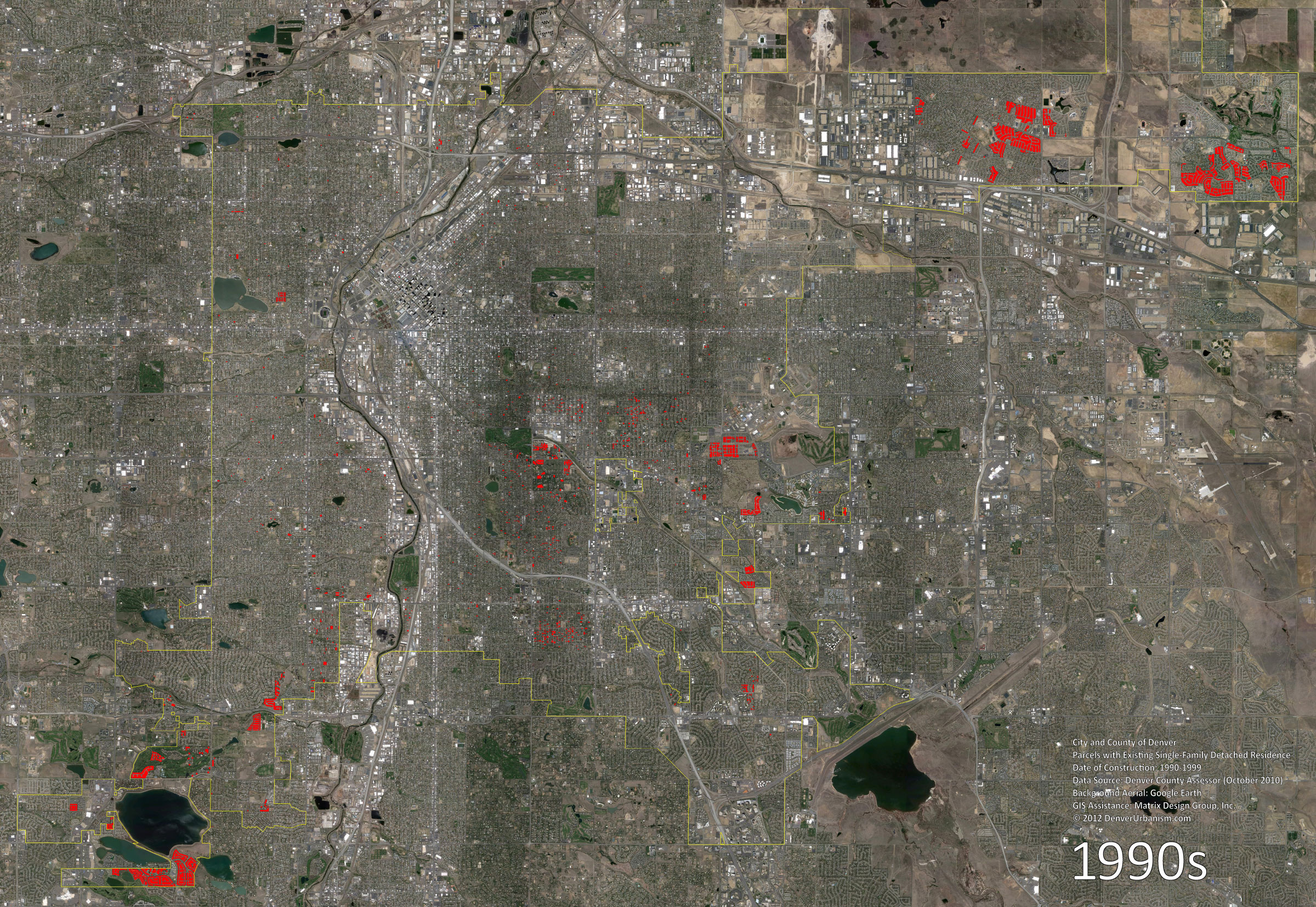

Here are the 1990s parcels colored in red over a current Google Earth aerial:

Now we’re ready for Mark’s architectural photos and descriptions:

In the 1990s, the Neoeclectic phase of domestic architecture continued as Neoeclectic styles were the fashion while the modern Ranch continued to be constructed in large numbers attesting to its popularity and longevity.

1. Ranch. The style typically includes asymmetrical single-story homes with very low-pitched roofs and broad, sometimes rambling facades. The eaves may be either boxed or open with the rafters exposed and have a moderate or wide overhang. Both brick and wooden facades are common, sometimes in combination. Modest traditional detailing, usually loosely based on Spanish or English Colonial precedents is common and frequently entails decorative shutters and porch-roof supports. Ribbon windows are common as are large picture windows in living areas. Here are some examples from the decade of the Ranch and its variants. Top left (Gateway/Green Valley Ranch), top right (Indian Creek). Bottom left (Indian Creek), bottom right (Gateway/Green Valley Ranch):

2. Neoeclectic / Neoclassical Revival. The style features the full-height columns from the preceding Neoclassical style and applies them to a variety of house forms. Similar to other Neoeclectic styles, most examples show little concern for historically accurate detailing. Earlier versions were typically single-story while more recent adaptations are commonly two-story (Cherry Creek):

3. Neoeclectic / Neo-Mediterranean. The style is loosely based on earlier Italian Renaissance, Spanish Eclectic, Mission, or Monterey precedents. Common features include tile roofs, stucco walls, and round-arched windows and doorways. Left (Belcaro), right (Cherry Creek):

4. Neoeclectic / Neo-French. Perhaps the most dominant Neoeclectic style, Neo-French typically features steeply pitched hipped roofs and through-the-cornice dormers. Doors and windows are frequently round or segmentally arched (Belcaro):

5. Neoeclectic / Neocolonial. A very free adaptation of the preceding Colonial Revival style showing less concern for copying the more historically precise Colonial prototypes. Metal windows and widely overhanging eaves are common with free interpretations of Colonial door surrounds, colonnaded entry porches, and dentiled cornices. Roof pitches differ in that they may be either steeper or lower than earlier Revival examples. Left (Lowry), right (Belcaro):

6. Neoeclectic / Neo-Victorian. More rare than the other traditional revivals, Neo-Victorian was one of the last neoeclectic styles to appear. Most examples feature free interpretations of Queen Anne spindlework porch detailing and mimic the cross-gabled hipped-roof form commonly seen in earlier prototypes. Left (Lowry), right (Washington Park West):

7. Neoeclectic / Neo-Tudor. The style, similar to its Tudor predecessors, characteristically features dominant front-facing gables with steeply pitched roofs. Decorative half-timbering detailing is nearly universal and windows are grouped and sometimes include diamond-shaped panes. As with other Neoeclectic styles, little attention is paid to precisely copying its Tudor antecedents (Belcaro):

8. Late-Modernism. As described previously, late Modernism refined and reformulated earlier Modern concepts and revived disfavored Modernist features such as radial corners, belt courses, and glass block. Defining characteristics include a horizontal orientation, use of industrial materials such as concrete, ribbon windows and belt courses, hooded or deep set windows, large areas without windows, no ornament, decorative use of functional features, walls are eaveless or with boxed or cantilevered eaves, and flat or shed roofs (Cherry Creek):

9. The following are some examples of infill from the 1990s in the Washington Park neighborhood:

Next time, we’ll explore our last full decade… the 2000s!

How does one classify a historic home that has been significantly changed or “pop-topped”? Is it still considered to be of the style that it originally was, or does it become “neoeclectic” at that point?

This is my opinion, but it really depends on the house and the amount of change. A house built in 1911 and modified in 2011 will always be on the record as such. if the addition is subtle and sensitive to the historic quality and character of the building, I personally see no reason not to refer to it in its original style. Becasue I believe it is the original style that would dominate in that case. If, however, it is a significant redo then it should take on its neo-whatever name since it is largely Neo (a.k.a. new). Of course, to me Neoeclectic is another way of saying “What were they thinking?” And, as we all know, there are a boat load of pop-tops that fit in the Neoeclectic description — Not that there’s anything wrong with that!

It almost seems like “neoeclectic” is the residential equivalent of “post-modern.” Basically, do whatever you want and borrow whatever you want from historical styles, but pay no mind to being overly accurate. There is almost nothing out there right now that represents a TRUE stylistic revival in the historic sense of the word.

I sort of agree with you on that because both styles feel intuitively wrong to many people. However, I think that even in post modernism, there was an attempt to reinterpret classical forms and styles in a post-modern way that still demonstrated the importance of proportion, scale, and size. On a PoMo building, I could usually see the connections with the past, even if they were wildly new. However, in neoeclectic, there is no connection to anything. Forms are randomly selected, awkwardly proportioned, placed at the wrong places on buildings, and generally executed in a clumsy manner.

The problem is that the neoeclectic “designers” see the forms but don’t understand what about them makes them successful. They want a round tower and just slap it on the building not knowing how tall it should be, how it relates to the front door, or how it engages the walls and materials around it. Then it just looks bad and no one really knows why. And in fact, most of the general public may not even realize it unless they compare it to something done well. This is why so many (but not all) contractor and drafter based designs tend to not look right. These folks often do not understand these things or know how to incorporate them into a design.

Not that being an Architect absolves them of these sins, but they certainly should have the tools to work within that framework. Unfortunately, most people want their Macy’s quality at Walmart prices. I guess you get what you pay for.