In this special DenverUrbanism series exploring the geographic and architectural attributes of Denver’s single-family homes, we’ve arrived at the 1970s. For previous installments, please use the links below:

1870s (plus series introduction)

1880s

1890s

1900s

1910s

1920s

1930s

1940s

1950s

1960s

The 1970s was Denver’s twelfth full decade as a city. Denver’s annexation battles with its suburban neighbors reached a climax in the 1970s. Denver continued its aggressive expansion, with much of the newly annexed land located to the southeast into Arapahoe County along I-25, and to the southwest into Jefferson County in the Southwest Plaza area. From 1970 through 1972, Denver annexed 2,349 acres or approximately three and a half square miles. Then in 1973, Denver annexed a whopping 9,575 acres (about 15 square miles)—the most the city ever annexed in a single year—although some of that land was eventually de-annexed after lengthy court battles. However, it was the statewide passage of the “Poundstone Amendment” to the Colorado Constitution in 1974, which required Denver annexations to be approved by voters in the county losing the territory, that effectively brought the expansion of Denver’s borders to a halt.

From 1970 to 1979, approximately 8,000 single-family detached homes were built in Denver, the fewest number since the Depression-era 1930s. Despite the city’s territorial expansion through annexation and the construction of these new homes, more people moved out of the city than moved in during the 1970s. Denver lost population for the first time in its history, dropping from a census count of 514,678 in 1970 to 492,365 in 1980, a 4.3% decrease, and leaving Denver with a population roughly the same as its 1960 census total. Crime, court-ordered busing, and urban blight took its toll as thousands of people left Denver’s denser historic neighborhoods for the modern sprawling suburbs. Those ornate Queen Anne, Italianate, and Romanesque homes from the late-19th Century, by then approaching one hundred years old, were falling into disrepair. Things historic were passe and “modern” was in. The city struggled, and it clearly had lost the suburban housing game to the suburbs.

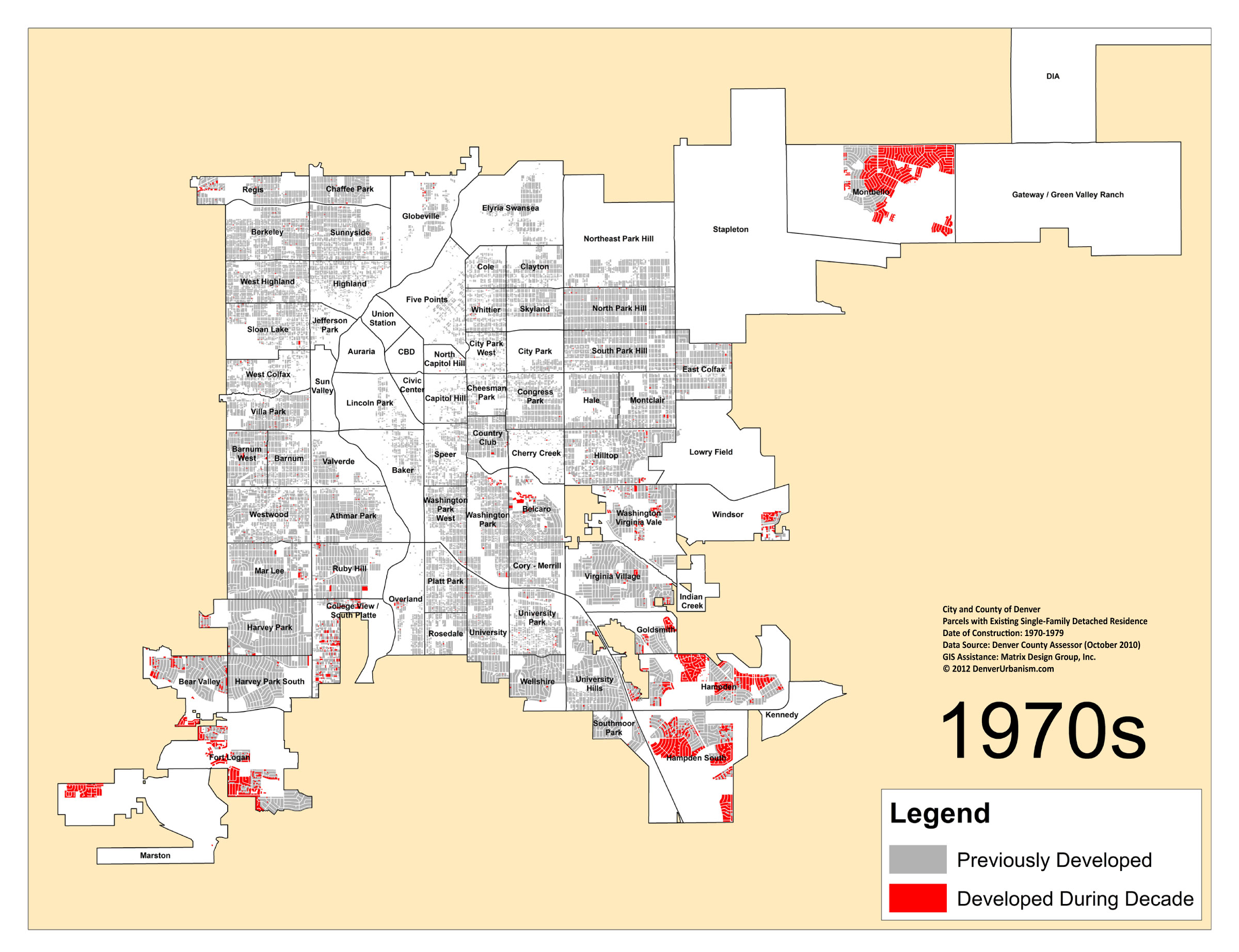

Here’s our Denver Neighborhoods Map showing the city’s single-family residential growth in the 1970s. Parcels with single-family homes built during the 1970s that remain in existence today are colored red. Parcels with homes that were built in a previous decade that remain in existence today are colored gray. Click/expand to see images at full size.

By the 1970s, growth in Denver was concentrated into a handful of new neighborhoods mostly on the city’s outer edges. As a result of those annexations to the far southwest, the first homes in the Marston neighborhood were developed, and more growth occurred in the Hampden and Hampden South neighborhoods. To the northeast, Montbello saw major expansion during the 1970s as the city’s first neighborhood east of Stapleton International Airport.

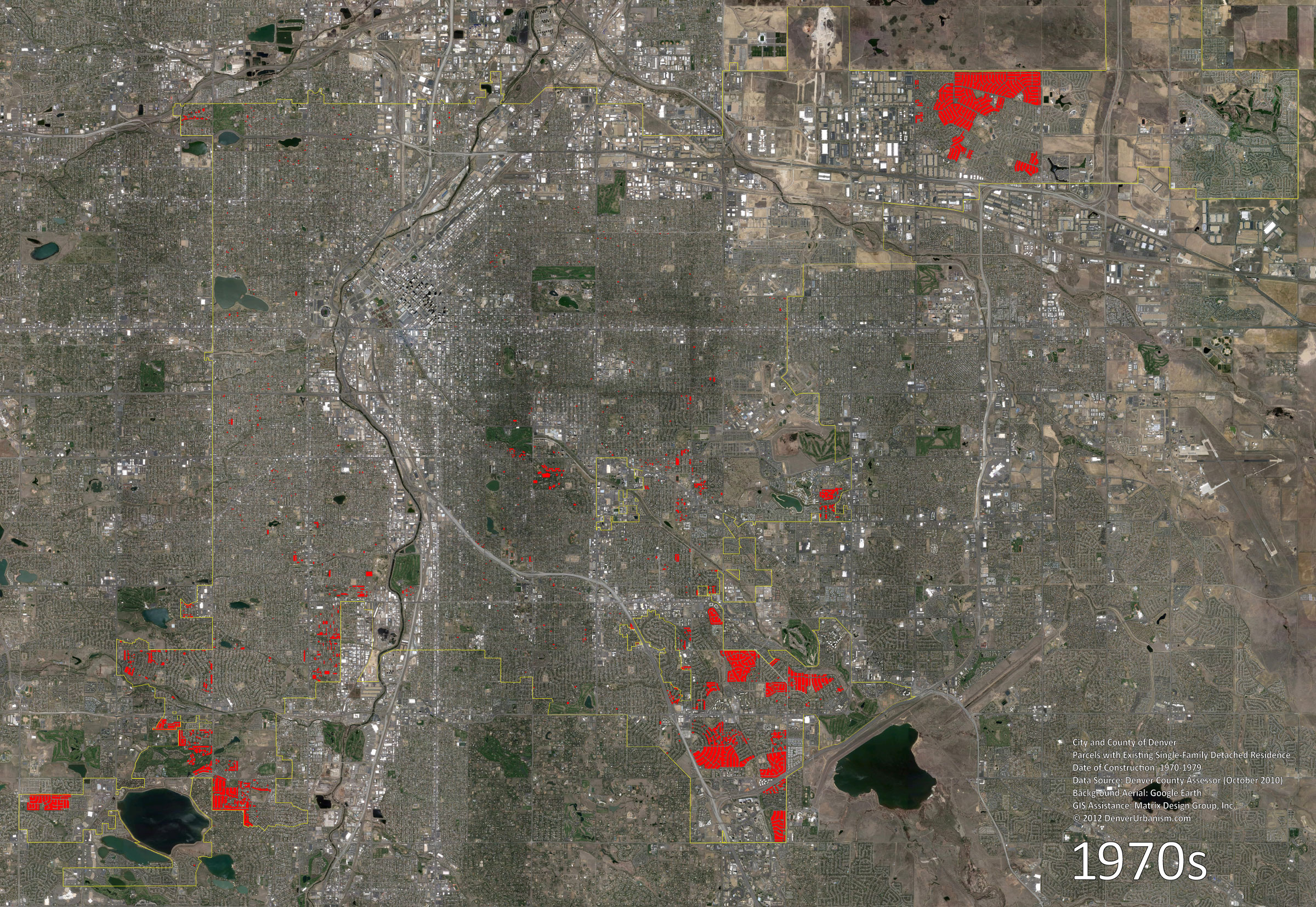

Here are the 1970s parcels colored in red over a current Google Earth aerial:

Ready for some 1970s architecture? Here are Mark’s photos and style descriptions:

The modern ranch remains the dominant building form in the 1970s while the popularity of Neoeclectic houses grows rapidly during the decade after a modest beginning in the late 1960s.

1. Ranch. As previously detailed, the Ranch style features asymmetrical single-story homes with very low-pitched roofs and broad, sometimes rambling facades. The eaves may be either boxed or open with the rafters exposed and have a moderate or wide overhang. Both brick and wooden facades are common, sometimes in combination. Modest traditional detailing, usually loosely based on Spanish or English Colonial precedents is common and frequently entails decorative shutters and porch-roof supports. Ribbon windows are common as are large picture windows in living areas. Some examples from the decade of the Ranch and its variants. Top left (Hampden South), top right (Windsor). Bottom left (Goldsmith), bottom right (Hampden South):

2. Brutalism. Closely related to the Formalist style, Brutalism consists of dense compositions of both square and rectangular volumes. The effect was to create a more visually complex building through artful repetition of functional features rather than through ornament. Defining characteristics include a vertical orientation, over-scaled proportions, deeply recessed windows, use of cast-in-place concrete or aggregate, use of self-sealing metals, thick vertical piers, eaveless walls or coping at top of walls, use of smoke or gray tinted glass, and flat roofs. Both photos from Hilltop:

3. Late Modernism. Similar to earlier Modern styles, Late Modern architecture was reductive and functionalist and largely constituted an updating of those styles. Late Modernism refined and reformulated earlier Modern concepts and revived disfavored Modernist features such as radial corners, belt courses, and glass block. Defining characteristics include a horizontal orientation, use of industrial materials such as concrete, ribbon windows and belt courses, hooded or deep set windows, large areas without windows, no ornament, decorative use of functional features, walls are eaveless or with boxed or cantilevered eaves, and flat or shed roofs. Left (Cherry Creek), right (Washington-Virginia Vale):

4. Formalism. This style reintroduced to Modern Architecture a classicism through regular and sometimes symmetrical massing, in contrast to the International Style and its irregular, asymmetrical form. Formalism was to be superseded by Post-Modernism. Characteristics include a vertical orientation, spandrels that vertically link windows, recessed windows, vertical piers, eaveless walls or coping at the top of walls, flat roofs, and may include decorative sun-screens, screen walls, or planters (Montclair):

5. Neoeclectic/Neo-Tudor. The style, similar to its Tudor predecessors, characteristically features dominant front-facing gables with steeply pitched roofs. Decorative half-timbering detailing is nearly universal and windows are grouped and sometimes include diamond-shaped panes. As with other Neoeclectic styles, little attention is paid to precisely copying its Tudor antecedents (Fort Logan):

6. Neoeclectic/Neo-Mediterranean. The style is loosely based on earlier Italian Renaissance, Spanish Eclectic, Mission, or Monterey precedents. Common features include tile roofs, stucco walls, and round-arched windows and doorways (Windsor):

7. Neoeclectic/Neo-French. Perhaps the most dominant Neoeclectic style of the decade, the Neo-French typically features steeply pitched hipped roofs and through-the-cornice dormers. Doors and windows are frequently round or segmentally arched (Fort Logan):

8. Neoeclectic/Mansard. As previously defined , the style first appeared in the ‘60s and was named for its characteristic roof and was frequently used for commercial buildings and apartment houses as well. Builders realized that an inexpensive way to gain a dramatic decorative effect was to slightly slope the upper wall surfaces and cover them with decorative shingles and detailing. Left (Hampden South), right (Bear Valley):

9. Shed. The style features a multi-directional shed roof that in shape appears to be one or more shed roof elements (sometimes with additional gabled roof forms) joined together creating an effect of colliding geometric shapes. Wall cladding is typically wood-shingle or board siding. Roof-wall junctions are smooth and simple and have little or no overhang. Entrances are commonly recessed and obscured. Windows are generally small and asymmetrical. The overall effect is of prominent diagonals, contrasting shapes, and multiple massing. Left (Hampden South), right (Goldsmith):

Coming soon… the 1980s!

I absolutely love this series! It would be great to see a similar series on Denver’s commercial/retail/mixed use architecture through the years to complement this one!

When this series first started, I wondered what on earth Ken was going to do once we reached the more recent decades. I had this apparently ill-conceived idea that all new housing was bland tract housing by about 1970 or so – unless you were wealthy enough to buy a plot of land, then commission some custom mansion for it. But most of these homes look like 2000-ish square-foot, middle class homes. I guess my hatred for suburbia has allowed me to develop this hyperbolic idea that every last home built in the US during the 70’s was pretty much an exact replica of that ranch house in the first pic, lol.

I’m glad this series has been enlightening. I too have learned a lot about the diversity of Denver’s architectural styles, particularly in the later decades, through Mark’s photography and descriptions.

I realize that this blog is really only focusing on exterior architecture, but it may be worth mentioning that one of the real plan inventions of the 1970’s was the split-level and multi-level house. I can tell by looking that the Bear Valley house in section #8 is a multi-level home as the windows indicate a floor slightly below and slightly above the garage/entry level and there is another level above the garage. A split-level (not pictured here anywhere that I can tell) would have just three levels: entry/garage level, upstairs and downstairs)

Prior to the 70’s most houses had a main entry on the main level of the house; bedrooms and other service spaces might be upstairs or downstairs from this level. The Split-level and Multi-level homes beginning in the 70’s created much more ambiguity about which level was the “main level” but it was most commonly the one just above the main entry and garage. The invention of the split-level (or multi-level) created more dramatic entries and much more spatial complexity within American housing for the middle class. The ranches (and modernist usonian-type homes) of the previous decades had greatly opened up the floor plans on one level, but these homes opened the plans up into multiple levels (a trick that can make a small house seem much bigger than it actually is because you can see so much of it all at once)

Interestingly enough, the split-level and multi level plan seems to have fallen out of favor in the last decade (in favor of the more traditional house plan). I’m not sure why that is, perhaps it was all the stairs, or the fact that so few uses were located on the same level, or simply that it started to become “dated.” Whatever the case its an interesting chapter in American housing history.

The Bi-Level was a particularly hateful design. My contractor friend summed it up best “I make a thousand decisions every day. It sucks when I come home and have to make one more” (whether to go up or down).

For what it’s worth, some tidbits I remember (or misremember) from the period:

1. Many of the Late Modernism redevelopments in Wash Park and Cherry Creek were designed by Dick Crowther, or are copies of his stuff. He died just a few years ago at about age 99.

2. Muchow did a lot of the Mansard roof stuff as well as those huge A frames in Stokes Addition (1960s)

3. The deep-eaved ranches in Belcaro built by the Adams brothers (50s and 60s) will increase in popularity, if any of them survive this round of gentrification.

4. The ULTIMATE multi-level house was designed and built by Langdon Morris around 1967 in the 600 block of So. Garfield. Seven levels I think. I loved it.

I’ll be darn. I built the first house pictured in the “Shed” section. 1978.

Hated that style, but that’s what people wanted then.