Next in our investigation of the geographic and architectural attributes of Denver’s single-family homes is the decade of the 1950s. For previous installments in this series, please use the links below:

1870s (plus series introduction)

1880s

1890s

1900s

1910s

1920s

1930s

1940s

The 1950s was Denver’s tenth full decade as a city. Denver celebrated its centennial in 1959 as part of the broader Colorado “Rush to the Rockies” centennial celebration throughout the state. By the 1950s, suburbanization was in full swing and most of the growth was occurring outside of Denver’s borders. From 1902—when Article XX of the Colorado State Constitution was adopted that created the City and County of Denver—until 1940, the city’s boundaries did not change. For those 38 years, the city’s growth occurred entirely within the roughly 59-square mile area established in 1902 as the City and County of Denver. In 1941, Denver began annexing new territory on its periphery. From 1940 through 1949, Denver annexed 4,907 acres of land, or approximately 7.7 square miles, much of that for the expansion of Stapleton International Airport. In the 1950s (1950 through 1959), Denver annexed 4,736 acres of land, or about 7.4 square miles. Nevertheless, Denver was capturing through annexation only a small percentage of the suburban growth that was occurring throughout the metropolitan area at that time. Stay tuned for the 1960s and 1970s, however, when Denver really got serious about annexations.

Anyway, the 1950s is Denver’s top decade for the number of single-family homes built in the city. From 1950 to 1959, approximately 31,000 single-family detached homes were built in Denver, almost double the second-highest decade, the 1940s, with its 16,000 homes. Combined, the number of single-family detached homes built in Denver in the 1940s and 1950s—representing just 13% of the city’s 153-year existence—constitutes almost 37% of the city’s existing single-family detached housing stock. During the 1950s, Denver’s population increased by about 78,000, from 415,786 in 1950 to 493,887 in 1960, a 19% increase.

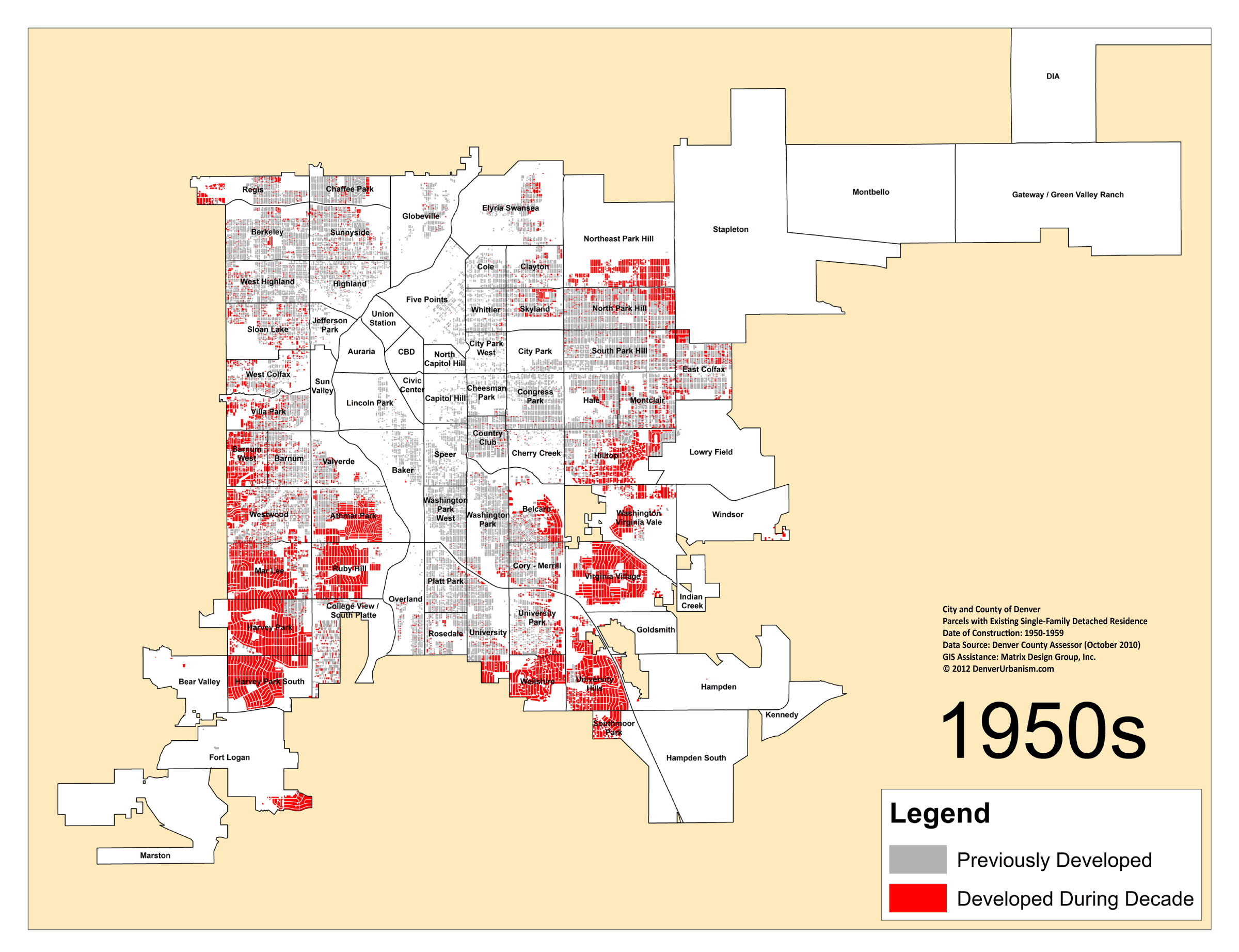

Here’s our Denver Neighborhoods Map showing the city’s single-family residential growth in the 1950s. Parcels with single-family homes built during the 1950s that remain in existence today are colored red. Parcels with homes that were built in a previous decade that remain in existence today are colored gray. Click/expand to see images at full size.

That’s a lot of red!

We saw a preview of this in the 1940s, but the 1950s represents the era when subdivisions were, for the most part, built out in their entirely within the decade. Looking back at our maps from the 1880s through the 1930s, the red parcels representing new homes are generally scattered around—a few over here, a few over there—like confetti tossed into the sky. Certainly, some neighborhoods were hotter than others, but there was still a general pattern of dispersion to Denver’s single-family housing growth. Neighborhoods like Berkeley, Globeville, Washington Park, and many others saw homes built within their boundaries over the course of five or six decades. In the 1950s, we start to see whole neighborhoods come online all at once. Big chunks of Southwest Denver (Barnum West, Westwood, Athmar Park, Mar Lee, Ruby Hill, Harvey Park, and Harvey Park South) were developed in the 1950s. Similarly, a broad front of development occurred along Denver’s eastern flank in the Wellshire, University Hills, Belcaro, Virginia Village, Washington-Virginia Vale, Hilltop, and Northeast Park Hill neighborhoods. Only those neighborhoods closest to Downtown saw no growth during the 1950s.

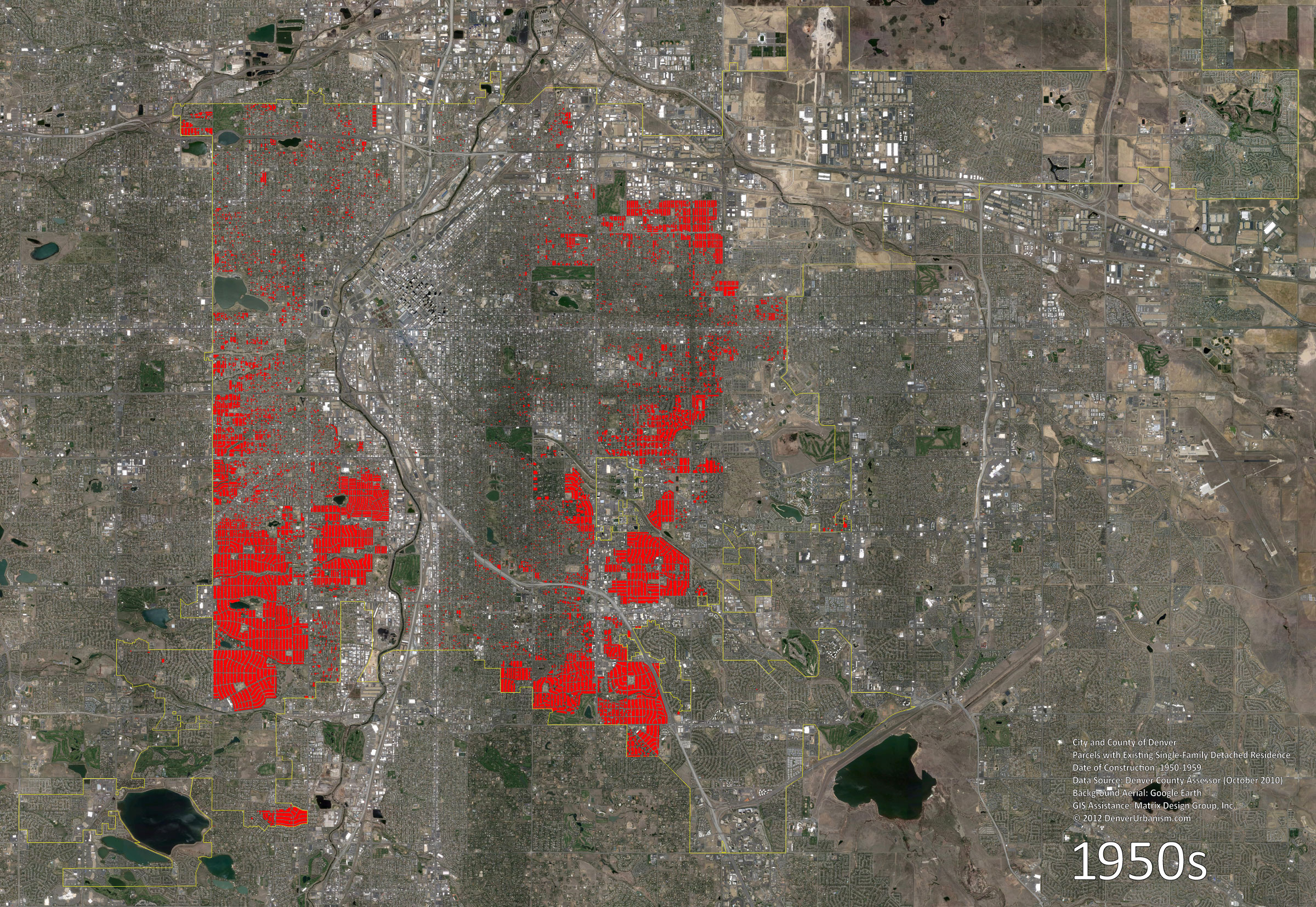

Here are the 1950s parcels colored in red over a current Google Earth aerial:

Now, let’s take a look at the style of homes built during the 1950s. Here are Mark’s photos and architectural descriptions:

The ubiquitous Ranch house rose to prominence this decade. Originated in the 1930s by California architects, it gained in popularity during the 1940s to become the dominant style throughout the country during the ‘50s and ‘60s and, indeed, are still popular today. The style is loosely based on early Spanish Colonial precedents of the American southwest, modified by influences borrowed from the Craftsman, Bungalow, and Prairie style modernism of the early 20th Century.

1. Minimal Traditional. The immediate predecessor of the Ranch house, as described previously, the style was a simplified form loosely based on the previously favored Tudor style of the preceding two decades. Featuring dominant front gable and chimney, the steep Tudor roof pitch is lowered and the façade is simplified with the majority of the traditional detailing omitted. The eaves and rake are close (East Colfax):

2. Ranch. Typically asymmetrical single-story homes with very low-pitched roofs and broad, sometimes rambling facades. The eaves may be either boxed or open with the rafters exposed and have a moderate or wide overhang. Both brick and wooden facades are common, sometimes in combination. Modest traditional detailing, usually loosely based on Spanish or English Colonial precedents is common and frequently entails decorative shutters and porch-roof supports. Ribbon windows are common as are large picture windows in living areas. Top left (Belcaro), top right (Cory-Merrill). Bottom left (Harvey Park South), bottom right (Belcaro):

3. Split Level. A multi-story variation of the dominant one-story Ranch house. The style retains the horizontal lines, low-pitched roof, and overhanging eaves of the Ranch, but added a two-story unit bisected by a one-story wing resulting in three floor levels (Mar Lee):

4. Raised Ranch. A two-story variation of the Ranch with the lower story at ground level or partially submerged below grade, and typically asymmetrical with a low-pitched side-gable roof with large double-hung, sliding, and picture windows. They usually feature little decorative detailing, aside from decorative shutters and porch-roof supports (Belcaro):

5. Second Phase International. As described from the previous decade. the style encompasses functionalism and reductivism, in that the design is influenced by functional concerns expressed with austere simplicity. Common characteristics include a horizontal orientation with strong secondary verticals, eaveless walls, large sections with clear or tinted glazing, glass or metal curtain walls, rectilinear conception of the structure’s volumes, no ornament, flat and unorthodox roofs, and the use of the cantilever. Some examples of the style from the decade, left (Cheesman Park), right (Wellshire):

6. Usonian. The Usonian style is based on Frank Lloyd Wright’s concept of naturalism. Defining characteristics include a horizontal orientation, cubist conception of the building’s volumes, ribbon, corner, and clerestory windows, traditional materials (wood and stone), the use of similar materials inside and out, geometric ornament, overhanging eaves and the use of the cantilever. Several examples from the 1950s, left (Hilltop), right (Wellshire):

7. Colonial Revival. A later example that displays the changing postwar fashions that led to a simplification of the style in the 1940s and 1950s. Later examples are most often the side-gabled type that feature simple stylized door surrounds, cornices or other details that merely suggest their colonial precedents rather than closely replicating them. The home features a three-ranked facade with a gabled entry portico with a curved underside (Belcaro):

8. Cape Cod. A sub-type of the Colonial Revival style, this home features a simple rectangular shape with a steeply-pitched side-gable roof. 20th Century Cape’s typically place the chimney at one end instead of the center and have large dormers, decorative shutters and often include an additional room or garage attached to one side (Belcaro):

That’s it for the 1950s! Up next… the 1960s.

July 15 Update:

By popular request, here’s an additional section on 1950s architecture from Mark, featuring another one of the decade’s key architectural styles:

9. Modern/Contemporary. A vernacular example of what were essentially single-story ranch houses made popular by California developers Joseph Eichler and George and Robert Alexander. Eichler and Alexander reinvented the style and created a revolutionary new approach to suburban tract housing and builders across the country imitated their designs. Common characteristics include post and beam construction, concrete slab foundations, long front facades with an attached carport, floor-to-ceiling windows, sliding glass doors , flooring with radiant heat, exposed beams, and an open-air entry courtyard. Left (Hilltop), right (Virginia Village):

Yikes. Of course, all of that red is made more dramatic by the fact that a “typical” lot size in Harvey Park South is 8,000-12,000 square feet; doubled from a few decades prior.

As always, thanks Ken (and Mark) for this great series!

No Krisana Park “Eichlers” pictured?

You neglected to include what I call the “Concrete Block Box.” There are 12 houses on my street (1300 block of Perry) all built in the 1950’s that are nothing more than a 30’x30′ square home constructed entirely of concrete block; most don’t even have siding on the exterior. There are many more are scattered throughout the southwest section of the West Colfax Neighborhood. These homes are completely devoid of any character whatsoever, but on the other hand they certainly couldn’t be more durable.

In an assessment 1950’s homes I think one should also include perhaps one of the worst housing creations of the decade, what I call the “Forward-Rear off-set Duplex.” These houses make up a huge portion of the NE Park Hill housing stock but can be found scattered throughout other older neighborhoods. Essentially instead of the side-by-side duplex common in the 1920’s these homes divide the property into front and rear units slightly offset from each other so that each unit gets a street front entry. While this housing plan must have seemed a pleasant and affordable way to provide housing for lower middle class residents of the city in the 1950’s (and for the most part remain affordable to this day) they have some major design flaws that make them less than desirable places to live.

First, these units can be magnets for crime as the entry to the rear unit is hard to see from the street and usually lacks any surveillance from the front unit. The person in the front unit can’t tell whether a person cutting across their front lawn and going to the back should or shouldn’t be there (and if something does go down, they generally can’t see it happening)

Second, these homes can lead to conflicts among tenants. Since “ownership” of the front and back yards are often poorly defined there are questions of who is responsible for maintenance of essentially shared space which can lead to tension between owners or general disinvestment in landscape maintenance all together. Another issue is that there is usually not one straight line dividing the two units, rather the units nestle together in funny yin-yang sort of way. This makes exterior remodeling (desired by one tenant) even more difficult than side-by-side duplexes. Furthermore, the front unit’s phone, cable and electrical service sometimes needs to go through the attic of the rear unit, creating a strange access issue between neighbors.

Finally, these homes break the traditional front-yard back-yard roles of the majority of the american housing stock (that is presentation in front, and functional play and storage space in the rear). Since the front unit only gets a sliver of the back yard, their front yard often becomes their back yard complete with all the toys, furniture, garbage cans, etc. that are usually in the back. All this clutter up front can make the neighborhood look trashy and may not provide the kind of “presentation” that the owner of the rear unit might like (this may contribute further to the tenant conflicts mentioned above).

Luckily, as with most of the homes built in the 1950’s these duplexes are constructed with high quality craftsmanship and materials and have stood the test of time, rarely looking rundown. In that regard they will remain solid affordable housing units for a long time to come. Unfortunately they’ll always remain less-than-desirable places to live, dragging down their neighborhoods with them.

That’s interesting Chad. Thanks!

These houses are the pretty ones! What happened to the ugly ones like my dad grew up in in Westwood? You know, the “crackerbox” style all done up in Johns-Manville siding?

Or better yet, those nasty asbestos shingles.