This is post number three in a four-part series on Denver’s streetcar legacy and its role in neighborhood walkability. For the introductory post, click here and for the second post, click here. To get the most out of this post, I recommend taking a look at and selecting the Streetcar Legacy section on the sidebar.

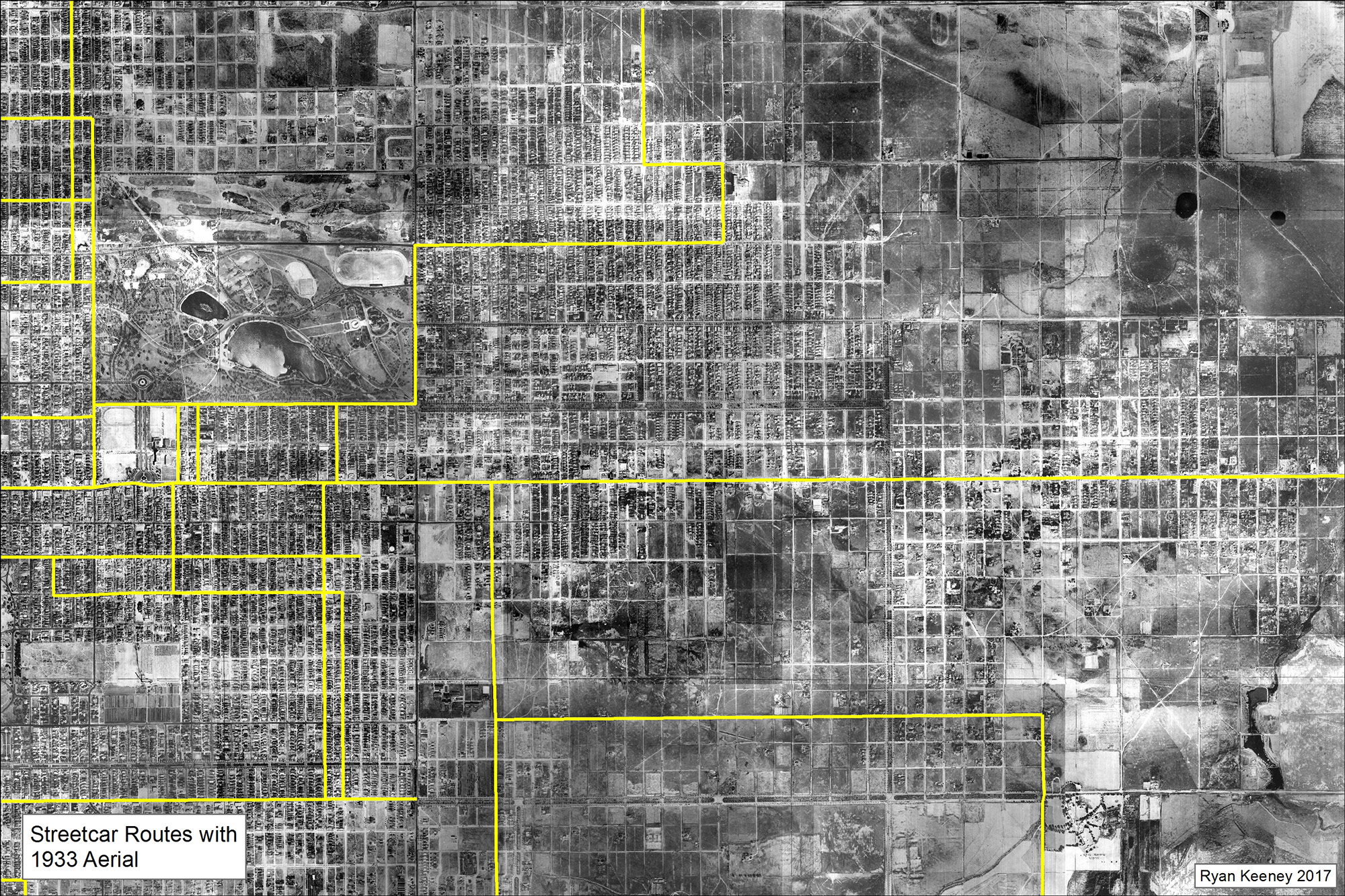

Just as cars and highways shaped the urban form of modern American metropolitan areas by encouraging dispersed patterns of development, a similar process occurred with the streetcar in the first half of Denver’s history. Denver once existed as a very compact city with development reaching only as far as the edges of the modern central business district. When the streetcar entered the picture, the footprint of the city began to expand along the streetcar routes. As late as 1933 (first three images below on left) the development of the city was tightly bound to the streetcar lines. The city existed as a grid of streets with rows of buildings clustered tightly about the streetcar lines, with open land only a few blocks beyond.

The difference between rail transit and highways lies in the degree of dispersion. With the streetcar, people had to walk to and from the stops. This naturally limited this distance that buildings could be built from the stops to no more than about a half mile, often less. With highways (below far right) this is not the case. When a motorist exits a highway, they continue to drive until they reach their final destination, where they can then almost always park on site. Walking is hardly a factor anymore, so development can spread farther from the highway without any travel time sacrifice.

So walking is part of any transit trip. You have to walk from your origin to the closest transit stop, and from the transit stop where you get off to your destination. This was daily life for most Denverites in the first half of the city’s history and the built environment was configured to facilitate this with a tightly gridded street pattern clustered about the streetcar lines. Additionally, commercial centers also developed on the same streets as the streetcar right-of-way. This allowed the people walking to and from the streetcars to purchase goods and services before continuing on their way.

These commercial nodes capitalized on the foot traffic generated by the streetcar to succeed. As a result, every neighborhood in the city had a vibrant commercial center and nearly every household in the city was within walking distance of most of their daily needs.

Today, the streetcars are gone, but many of these commercial centers remain. The most obvious examples are the continuous corridors on arterial streets like Broadway and Colfax, but they are also scattered on more neighborhood-oriented streets like South Pearl near Florida, Gaylord at Mississippi, and Tennyson at 41st. It is these neighborhood commercial nodes that are particularly special because they lack the noisy and dangerous automobile traffic of bigger streets, and are therefore more pleasant for the pedestrian. For my master’s capstone project, I mapped every single one of them.

There are no official terms that describes these developments that I could find in any academic or urban planning literature. Therefore I have come up with my own: Streetcar Neighborhood Commercial Development, or SNCDs for short. I define them as clusters or corridors of pedestrian-oriented commercial buildings (POCBs) located adjacent to an abandoned streetcar line on a road with fewer than four vehicle lanes. So let’s break down the term. The “streetcar” refers to how the buildings once depended on the people who rode the streetcar. The “neighborhood” means that they are neighborhood serving. Therefore, big arterial roads with four or more lanes are excluded. Finally, the “commercial development” refers to how the buildings must contain some sort of business, whether it is a store or an office.

So what is a pedestrian-oriented commercial building (POCB)? They are the kinds of commercial buildings which are clearly built with pedestrian access in mind. Again I came up with my own criteria based on the patterns I saw in the buildings and defined them as two grades:

Grade One POCB: A commercial building built up to the sidewalk with no off-street parking setback. Side parking and lawns must consume less than 40% of the lot. Rear parking must not be larger than double the building footprint (below left).

Grade Two POCB: A commercial building with a sidewalk to building entrance parking setback less than the length of the building starting from the main entrance (below middle).

All other buildings are AOCBs, or automobile-oriented commercial buildings (below right).

While mapping them, I soon found that SNCDs come in many shapes and sizes. Because of this, I also decided to classify them based on their size, their provision of POCBs, and their health. I came up with six categories, shown in the text and images below. Going down the text corresponds to the images from left to right…

Exceptional Main Street: These SNCDs have a historic main street feel and consist of an approximately 600+ foot street segment with Grade One POCBs covering at least 75% of the street frontage on both sides.

Quality Cluster: More of a cluster than a corridor, these have > 75% of their street frontage lined with Grade One POCBs, but are not large enough to qualify for “main street” designation.

Mixed Main Street: These are large corridors, but have more automobile oriented buildings, Grade Two POCBs, and/or parking lots mixed in, causing the percentage of Grade One POCBs to fall below 75%.

Mixed Cluster: Same logic. Like a Mixed Main Street, but not large enough.

Corner Store: Any isolated POCB which contains multiple businesses. I did not account for those which only contain one business because they are harder to locate.

Degraded: SNCDs where most of the buildings are vacant, have been torn down, or have been converted to residential uses. This is not comprehensive, and there are certainly many more. In the final image below, you can see modern day Old West Colfax. It was once entirely lined with buildings, but now only a few remain, replaced by parking lots.

If you made it this far, I think you would benefit by looking at . The locations of all the SNCDs are mapped out and I have included additional goodies like information about the parcels contained within each one and links to Google Street View imagery. You can also access that 1933 aerial of the entire city.

Having mapped the location of every SNCD in Denver, I wanted to know how they affect the walkability of the neighborhoods in which they are situated. In the next and final post of the series, I will present an analysis of this in one of Denver’s neighborhoods.

Hey Ryan, well done. This is great work!

Your map, including clusters (especially of greens and reds) fits very closely to a map I shared with Ken a few months ago for a very long-run, fully built-out rail system for the Denver Metro Area including streetcars that touch some of those street ROWs – its a map I’ve spent a long time working on.

I actually interned on the RTD side of the FasTracks project during college and have spent a lot of time thinking about this subject – would love to chat about it with you and Ken sometime. Let me know if I can get your email address – I would be really interested to see what you think of my map having done this very thorough, far-more comprehensive project.

Great contribution!

I would love to get in touch. Scroll down to the bottom of the sidebar in the Story Map for my email.

“With the streetcar, people had to walk to and from the stops.” Yes, mostly because they didn’t have cars and streetcars were the best alternative – at that point in time! Once Ford rolled out the Model T and Model A, and especially following World War II, most people who could afford to buy cars (as they became more affordable) CHOSE to buy cars, simply because they were far more convenient. There really is no glamour, nor much convenience in having to wait for transit, especially if transfers are required. Time, for most people, has a value, and time spent in transit is viewed less favorably than time spent at any origin or destination. If we truly want to see public transit attract more riders, we need to focus far more on frequency and connections than on building rail lines as direct replacements for local bus lines. It all boils down to scarce, limited resources – for every streetcar line, 4 or 5 comparable bus routes can be implemented – finer grained, more-frequent schedules are more attractive, in the long run, than fancier vehicles / systems that run less frequently!

Funny, I bet your average Coloradoan spends about 1000x more time being stuck in traffic and trying to find downtown parking than they do waiting for public transit today. What you perceive as convenience is merely an illusion perpetuated by car manufacturers for 60-plus years.