By Camron Bridgford

Visionary is used to describe the process of thinking about or planning the future with imagination or wisdom. It’s often an overused word fraught with hyperbole—being described as visionary is a lofty title to live up to, but in the case of Urban Venture’s adaptive reuse project, Steam on the Platte, it feels rather fitting.

The vision behind Steam on the Platte, which DenverUrbanism introduced to its readers in 2015, was originally conceived by Urban Venture’s President Susan Powers, whose redevelopment company is well-known in Denver for investing in diverse urban properties that catalyze community and spur value through adaptive reuse projects prioritizing workforce housing, healthy living and sustainable practices. Powers sees opportunity where others may only see frustration—for instance, her company is also developing a master-planned community on the site of a former convent—and Steam on the Platte is no exception.

The site is located at 1401 Zuni Street, in an area that for many decades has been considered a no-man’s land of Denver’s industrial past, despite being less than three miles southwest of downtown. Until recently, Steam on the Platte has remained one of the few undeveloped, large-scale sites in Denver where, despite burgeoning development infiltrating the rest of the city, has stood neglected and without a vision for its future. This would have remained the case if Urban Ventures—alongside its partners tres birds workshop, White Construction Group and Wenk Associates—had not charted a different course for this 3.2 acre site, which includes a 65,000 square foot industrial warehouse, 400 feet of frontage on the South Platte River, and a unique history rooted in industry and immigration.

Originally settled in the 1880s, the Steam on the Platte site housed 24 residences belonging to Colorado’s first Russian Jewish immigrants. Having immigrated to southern Colorado to pursue farming—an occupation unrealized in their homeland—the settlers then moved to the west side of Denver alongside the South Platte River, where other eastern European Jews resided. Over the years, the site became the location for many businesses that went up and then went under, which Urban Ventures tracked through the use of Sanborn fire insurance maps. For a period of years—until a flood in 1965 forced its closure—the site’s large industrial warehouse was run by a rabbi and used for a rag baling business, which consolidated scrap textiles from around the region and shipped them to far-reaching places like Africa and South America.

Steam on the Platte’s history since that point has been complicated—and likely to many developers—daunting. At different turns, some of the buildings have served as a truck stop and gas station, the squatting home for a motorcycle gang, and an off-the-radar site for illegal pot growing. To develop the site, the industrial warehouse had to be bought from a man in prison for real estate fraud. Its past uses also meant finding nine gas tanks underneath the property’s surface, alongside the threat of additional environmental assessments potentially turning up costly deterrents. Ultimately, would may have caused other developers to shy away from pursuing Steam on the Platte as a smart investment did not detract Powers. And in the year since redevelopment of the site has begun, you can see that removal of the rubble has revealed a gem hidden beneath the surface.

Phase I of the redevelopment began in 2016 and will be completed at the end of this summer. It involved tearing down three buildings that did not add character to the site; converting the interior of the industrial warehouse, the centerpiece of the redevelopment, to prepare for tenant leasing; removing paint from the brick buildings to reveal their natural surface; and developing a courtyard that ties the site together through natural integration with both the bank of the South Platte River as well as an iron bridge that carries RTD’s W Line from downtown to Golden.

For Powers, two focal points attracted her to the potential for this site. One was its location directly adjacent to the South Platte, and her recognition that few properties facing the river still remain available. She also believes the project will integrate with neighboring Sun Valley’s redevelopment by serving as one of the first commercial developments in the area, in addition to capitalizing on its close proximity to the Auraria campus and the growth seeping westward from downtown.

The primary vision for Steam on the Platte is as use for commercial office space, but with a dedication to tenants that reject traditional downtown office space in favor of the off-the-grid and creative built environment that the site provides. Powers says that prospective or committed tenants have been primarily in the tech and design industries, with additional uses to include a restaurant, a coffee shop/café run by a local non-profit, and potentially, condominiums and a hotel.

Walking through the interior of the warehouse, which will be home to 8-10 tenants, the site is reminiscent of other expertly-conceived, adaptively-reused buildings in Denver. There is an attention to original materials, such as timber and brick; emphasis on the robust natural lighting flooding through 24 skylights; and plentiful iron and metal work that consistently reminds one of the building’s history.

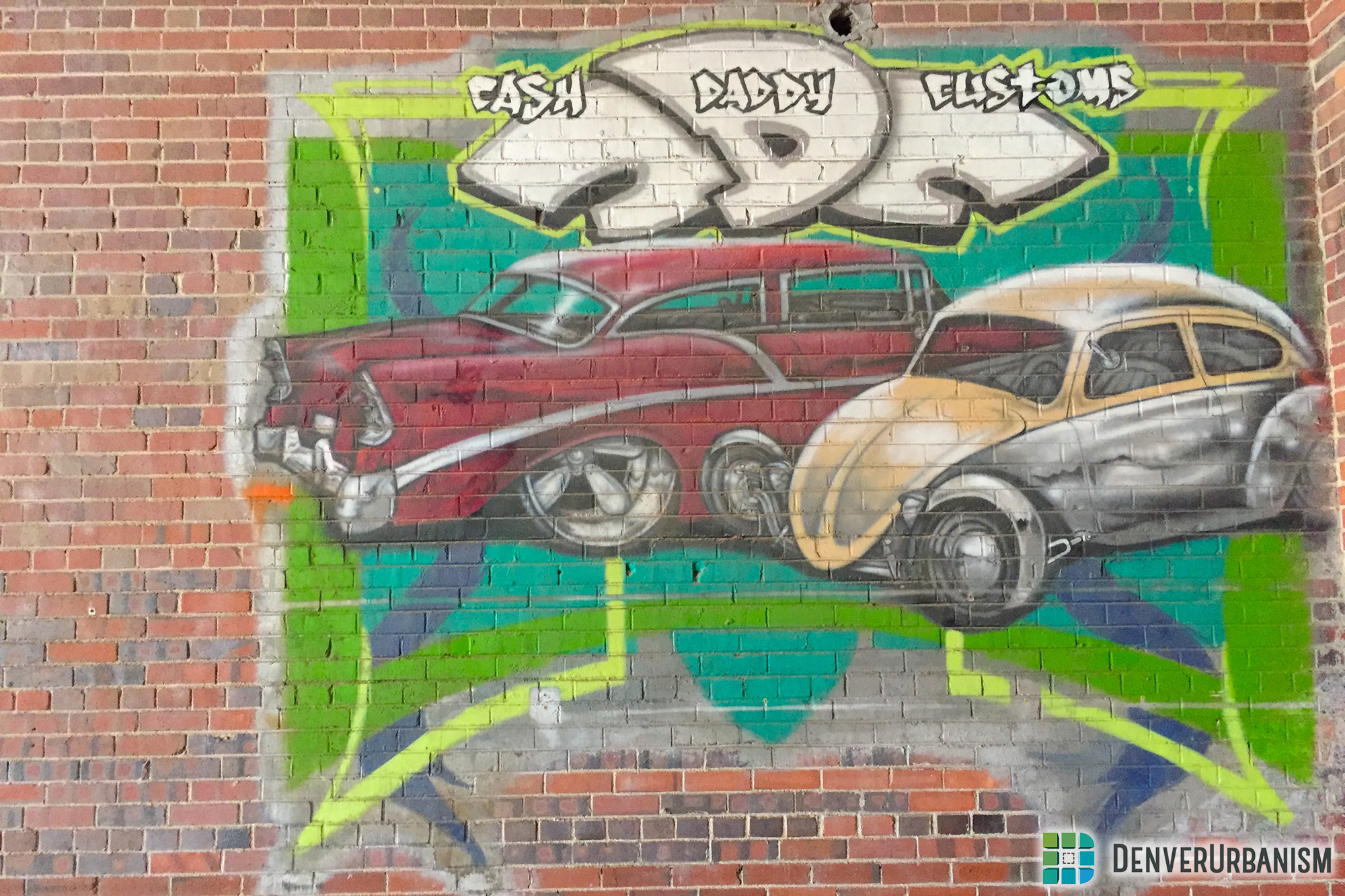

An original rag baling machine still sits at the center of the warehouse, and has been integrated with iron stairs that take a visitor to one of the building’s upper two floors. Other pieces of industrial machinery, rather than being removed, have been thoughtfully left in place to underscore work spaces and conference rooms. Glass walls are prevalent, allowing for the flow of natural light and a greater awareness for one’s surrounding space. Other details that are easier to miss but quietly tie the environment together—such as graffiti and ghost signs from previous businesses and building occupants, and walls covered in found object tiles–are discovered room by room.

At the entrance to the building’s construction site, a pile of found objects lays dormant but is being added to as new things are discovered. Objects are unearthed regularly, and have thus far included a hatchet head, glass medicine bottle, antique signage, glass door knob and whiskey bottles. Powers says the plan will be to display them at the entrance to the building so as to explain the history of the objects and their connection to the built environment.

While we sifted through the objects—some of which were unidentifiable in their use—one of the site’s construction managers adeptly commented that there are some stories that this building will never tell.

Tenants will begin occupying Steam on the Platte at the end of the month; remaining phases that include additional commercial office and residential space will take an additional three to four years to complete.

~~~

Camron Bridgford is a master’s candidate in urban and regional planning at the University of Colorado Denver, with a particular interest in the use and politics of public space as it relates to urban revitalization, culture and placemaking, and community development. She also works as a freelance writer to investigate urban-related issues and serves as a non-profit consultant.