On January 15th, a Mid-Century modern ranch style home in Belcaro known as the Wallbank/Parker House will meet its maker. The home, built in 1958, was designed by Tician Papachristou and Daniel Havekost. A huge brouhaha developed over the fate of this home when two individuals tried to save it from demolition in the 11th hour, after learning that the current homeowner planned to raze the structure in order to build a 21st century house on the site. While the homeowner saw little worth in saving the structure, others attempted to use a four-year-old city ordinance that allows any individual to seek landmark designation on potentially significant buildings. Needless to say, the homeowner was livid. You may read more about this issue in the Denver Post. This ordinance was passed in part to help stem the tide of mass demolitions occuring throughout neighborhoods like University Park and Hilltop, among others—neighborhoods that have changed overnight as housing that was seen as outdated, inferior or tacky has been replaced by “McMansions.” Of course, McMansion is in the eye of the beholder. This has pitted those who uphold private property rights at any cost against preservationists and older homeowners. As Assistant City Attorney Kerry Buckey said in the Denver Post, “You have property-rights people on one side saying, ‘It’s my house. I should be able to do what I want,’…. “On the other side you have the general history of Denver. Some of these structures, in a way, are owned by the whole city.”

This black and white scenario was brilliantly illustrated by the pro and con editorials in the Denver Post written by Vince Carroll and Joanne Ditmer.

Cities are ever-changing creatures, and we certainly cannot hold on to everything from the past. I certainly recall, however, a similar argument back in the late 1980s in a place we now call LoDo, when private landowners and building owners were livid that the city was considering a “hostile” historic district designation for their area. This foresight has benefited us today and has benefited those landowners. In fact, the success of LoDo has benefited Denver and the entire region.

The difficulty is in knowing what the future will bring. Will “we” lament the continuing loss of mid-20th-century architecture as it is currently being wiped away, much like the old Victorian mansions were in Capitol Hill in the 1950s? Or will “we” say good-riddance to it as a post-war atrocity? How does time and history affect our tastes or is it just the luck of the draw in what remains after everything else is demolished? Whether house, business, church or school, who should have a say in protecting the built environment in which we all share?

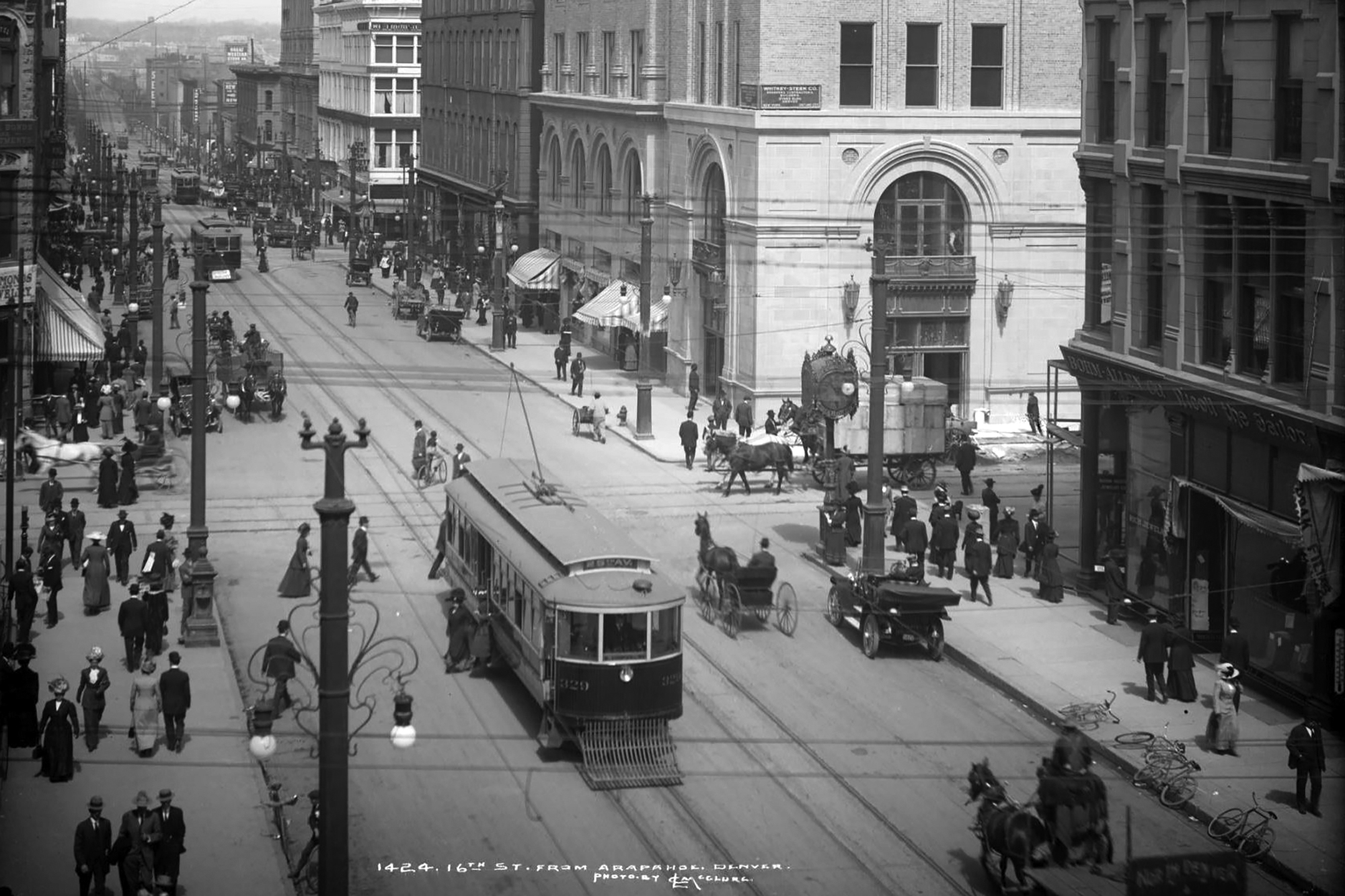

I do know one thing: if this law had been in effect back in 1965, and had I been alive, I would have been the first person to put this “hostile” designation into play in order to save the Tabor Grand Opera House at the corner of 16th and Curtis. Not only would it make that corner look better today (instead of the Federal Reserve Branch Bank), but it would have also saved a significant structure from Denver’s past, one that will never be replaced. At the time, no one with power saw this as a building worthy of saving for posterity. Today, its loss is generally lamented. The question therefore is: are the Wallbank/Parker House and other Mid-Century architectural examples on par with the Tabor Grand Opera House? I suppose only time will tell.

I have to take the side of the homeowner in this situation. If the neighbors take that much issue with his desire to build his dream home on the property than I suggest they take up a collection and offer to buy the home from him. While there may be as the article points out a handful of situations in which the people of the city have a legitimate claim, a house in suburban Denver is far from that case.

It’s worth noting that there are literally thousands of mid-century houses in metropolitan Denver, but our stock of large grand Victorian public buildings was always comparatively limited.

An interesting thought: If the Federal Reserve bank decided to leave their current location and a plan to build new condos or offices was put forth, would historicists step forward to try and save the building from demolition? It is currently one of the biggest deadzones on the mall and getting rid of it would help activate the street and make a more cohesive urban enviornment. However, it is an exemplary product of mid 20th century brutalism and destroying it would be ruining a bit of Denver’s history. The question gets more interesting if, rather than offices or condos, the developer proposes to rebuild the Tabor Opera house stone for stone. You can almost see the historicists’ brains short circuit. How does one decide what era in history gets preserved? If all past eras of design and thought are equal, as some people argue, that question can’t really be answered. However, if preservationists focus on quality of urban and architectural design rather than how a building represents the zeitgeist of a bygone era, the question becomes easy to solve. Tear the Fed building down and put something in its place that contributes more to the viability of the city. If the plan was to replace it with a parking lot or warehouse then I would argue to keep the Fed building. Many strip malls will be turning 40 or 50 soon, do they deserve to be bronzed and kept forever as a part of our civic fabric? I certainly hope not, tear them down and build something worth holding onto.

The home issue is a bit different as the argument is really about architectural style as both designs will probably contribute the same to the street fabric. Suburban homes act as suburban homes regardless if they are Victorian or mid century ranch.

I think Ralph has really hit the meta question nail on the head. IMO the preservation movement of the 20th Century did a big disservice to itself by framing the issue as one of historic preservation rather than as good urbanity. 20th Century preservationists didn’t want to save beautiful old buildings from the wrecking ball because they were *old* so much as they wanted to save them because they were *good*. Unfortunately, since they’ve been framing the issue as one of historic preservation for 50 years now, we’re stuck with the intellectual quandary of now trying to save bad buildings even though we really know better.

I’m glad to see that local councilman Charlie Brown has taken to heart the importance of toning down the overheated political rhetoric:

‘One of Denver’s most posh neighborhoods has been split by plans to demolish a home and an effort to save it — using a landmark preservation ordinance — that City Councilman Charlie Brown describes as “real estate terrorism.”‘

I trust that everyone on both sides of the debate will concede that that sort of comment is non-constructive, and is only likely to further polarize people. (Not that I expect any less from Charlie Brown, a specialist in polarizing citizens from behind a facade of center-right moderation.)

Back to the topic at hand, I think Ralph’s comments above are very sensible and on-target. I do think there could be certain instances where retaining a less functional building could be beneficial (would *anyone* at this point trade I. M. Pei’s May D&F building for the Adam’s Mark monstrosity?), and I do wonder if some districts would benefit from requiring that new buildings possess at least some minimal degree of architectural interest. Overall, though, focusing more on what buildings do, and less on precisely what they look like, is bound to benefit the city in the long run.

I think that it would be nice to see the Tabor Opera House rebuilt along with the Post Office, alongside some more modern development. Mid Century Architecture is being demolished today at an alarming rate and pretty soon we will be sorry for what we lost, just like with Victorian architecture in the 1940s-1970s. Even small towns on the opposite end of the country, such as my own, deal with the issue of Historic Preservation. My county, sadly, between 1950 and 2000 did not only get rid of many older buildings built in the Victorian era all the way through the 1950s, but what they replaced these buildings with was not as good as keeping the buildings there. The ugly 1970s Library, a not so great 1950s Motel near the Courthouse, metal shed fire departments, parking lots in many downtown areas, underutilized parks, and newer, ugly building replaced many masterpieces and community landmarks. We already are sorry for what we lost, but we didn’t learn apparently because we keep doing the same thing over and over again. The same thing for my area holds true for Denver. Hopefully, in the future, we can preserve Mid Century Architecture that is in its appropriate place, and get rid of some buildings like the Federal Reserve Bank and use the sites a lot better than they are being used presently. Denver is a city of the past, present, and future, and, like almost all cities out there, it can control what its future will be. But the city needs to learn to be smart so it can become a model for others out there.

I see it as somewhat of a generational issue. The early historic preservation movement was composed largely of individuals born between 1925 and 1945–the so-called “Silent Generation” (so called because those that were born after 1945 were a lot noisier). Their approach was simple: to save what was being lost, because in the 1960s and early 1970s, a lot was being lost all at once. Baby Boomers came along and refined the concept, and now younger people born after 1960 or 1970 are refining it even further, with the focus on urbanism more than mere preservation for its own sake. It’s an evolution.

As for the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City – Denver Branch (or whatever its official name is): the main argument in favor of keeping it is that it was the work (partially) of William C. Muchow, a leading Denver mid- and late-century modernist. His work also includes Park Central directly across Arapahoe. However: it’s not worth keeping. It destroys the fabric of this part of downtown, and I think it would be incredibly difficult to incorporate the building into a larger redevelopment of the block.

Seems to me more and more people these days think they have some kind of “right” to ride someone else’s pony.

Worth recalling that despite the loss of the Tabor Opera House, Denver now has the Ellie, once of the nation’s premier opera venues.

Historic preservation in its own right has only served to make our communities stronger since our brutal experience with mass urban renewal during the mid-20th century. However, comments herein do illustrate its ongoing controversial and arbitrary aspects. In Denver’s case, the city has only benefited from visionaries such as Dana Crawford who fought to save one block of Larimer Street from the wrecking ball, facing tremendous scorn for doing so at the time. Likewise, Denver City Council was vilified as “taking” away property rights when establishing the Lower Downtown Denver Historic District in 1988. In hindsight, they did the right thing, as the city and region have benefited. But results of these endeavors could have easily gone the other way. It is lucky for Denver that in these cases, preservation won out. Our clean skyscrapers and new CBD were the result of going the non-preservation route. This has made Denver what it is today. Was this all bad, tearing out the old for the new? As with anything, balance is the key. A static LoDo, wherein only the old could remain, with nothing new able to be built, would be too extreme. The same could be said about the Skyline Urban Renewal Project. In hindsight, DURA should have been more selective on what stayed and what was demolished. But it’s all moot now and there were many other factors occuring during the 1960s that led to the whole-scale demolition of our most historic core. We now have only pictures and the D&F Clocktower. Oh, and we have that Federal Reserve Branch Bank, which used to be located on 17th Street in another beautiful building that came down during the Skyline Project. The fact that this government building was allowed to relocate on the proposed 16th Street Mall (a known retail area) gives credence to the argument that you can’t always “trust” government decisions. Those planners of the time meant well, but made a poor decision. Does that mean the current building shouldn’t be preserved as a monument to mid-century modernist architecture? Were it located on a different street–perhaps. Were its architect Temple Buell or Frank Lloyd Wright–perhaps. This very arbitrary quality of whether a building is worthy of being saved or not also typifies why historic preservation has a bad reputation at times as well. But the fact is in its current location, it does more harm than good in the overall urban cohesiveness of that block. It’s a big deadzone on the mall and everyone knows it. Perhaps the answer is to move the Federal Reserve out of the building and incorporate this modernist “wonder” into a new mixed-use mega-project that would incorporate the building’s best elements into a neo-modern uber building of the 21st century. This adaptive reuse/historic preservation partnership would ensure that future generations couldn’t accuse us of demolishing the 20th century’s shining example of modernist architecture. Sometimes, buildings are only appreciated after they are gone, even ones so vilified by the present public. The Tabor Grand had no Dana Crawford or City Council to save it. It was seen as old and outdated by those with power. It was only lamented once it was gone. But I will agree that it is hard at this point to believe that any future population will condemn us for not saving the Federal Reserve Building for posterity.

As far as the topic that got all of this started–the demolition of the mid-century modern house in Bonnie Brae/Belcaro–I would argue that if it were the last of its kind, it should be saved. I would also argue that were its architect someone like Frank Edbrooke, Frank Lloyd Wright, William Lang, Temple Buell, etc., that there would be a much bigger fight to save it from a bigger and more interested audience. This illustrates once more the arbitrariness at times of preservation efforts when the saving of a building might more have to do with egos than with any particular intrinsic value of said building. I.M. Pei’s name on the hyberbolic parabaloid (May D & F) was not enough to save it and Denver is unfortunate to have lost that one. I am imagining the last house in downtown Denver at 1439 Court Place (the Curry-Chucovich-Gerash House) as all that’s left from the once grand residential area of lower 14th Street. Can you imagine if all of those buildings had been left in place with nothing ever changing there? It is a thought that excites preservationists like me but also points out the fact that in order for cities to thrive, they have to change with the times. If the 20th century taught us anything in the world of planning, it has shown us a need to balance out all interests for the best possible outcome. Extremes in any direction are not beneficial to anyone, whether that be a non-homeowner being able to stop the demolition of someone else’s house at the last minute or whether that be a city sitting at the sidelines as buildings are demolished to make way for parking lot after parking lot. We must find the balance.

The takeaway from the Belcaro debacle is that we should start making an inventory of potential historic homes in the city. It’s already been done with all the commercial buildings over 50 years old, right?

Then, it’s on the public record that the address may be protected under existing preservation law. If that had been done on this house, the new owner wouldn’t have been blindsided.

We’ve lost too much history, and thoughtful preservation rarely dashes the current owners’ dreams or damages his pocketbook. Thank God we kept 9th Street and Larimer St., and we should have kept MUCH more, as Shawn says above. Let’s make sure that a few MCM neighborhood streetscapes survive. Belcaro/Kentucky Circle has been lost, but there’s Dahlia Circle and maybe 700-900 S Jackson St. to save.

An inventory list starts the conversation for the residential sector. Historic designation shouldn’t be shoved on the current owners against their will, but most of them would gladly accept it. History has shown that it usually increases property values, so it’s a win for the owners, the neighbors and the city.